For more than two weeks from September 24 to October 12, through the collaboration of the Cultural Development Office, the Department of Philosophy and Humanities and the College of Arts and Social Sciences (CASS), the CASSalida Theater became home to “Badong: Salvador Bernal Designs the Stage,” an exhibit featuring the timeline and samples of major works of Salvador F. Bernal – the first and lone National Artist for Stage and Production Design.

His life and works as an artist are capsuled in this exhibit which is currently on a national tour this year from February to November in selected localities as part of the Lakbay Sining (Touring) Program of the Cultural Center of the Philippines Cultural Exchange.

Father of Theatre Design in the Philippines

“We have had National Artists for drama, music, dance and others but we never had a National Artist coming from those who work behind the scenes, until Bernal,” explained CASS Assistant Dean Sittie Noffaisah B. Pasandalan to Introduction to Literature students who visited the exhibit. Pasandalan added that Badong, started humbly but rose to become the most important figure in the Philippine stage design.

Born in 1945 to a family of that ran a terno shop, Bernal was exposed to the rudiments of fabric, cut and silhouette early in life. He finished his BS degree in 1966 at the Ateneo de Manila where he honed his talent as a poet and philosopher, acquiring the ability to read a text and imagine its theme as a visual conceit. in 1972 at the Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois where he took his Master of Fine Arts, he studied, practiced and handled art courses and craft of theatre design.

Briefly in 1973, as the acknowledged guru of contemporary Filipino theater design, Bernal has taught, translated and shared his skills with younger designers at the Ateneo de Manila University and the University of the Philippines, but soon plunged headlong and full-time into a life of design through the programs he created for the CCP Production Design Center that he himself conceptualized and organized, which until then was largely unchartered territory.

As a theater designer, Bernal has designed more than 300 productions distinguished for their originality since 1969. He also dabbled in the movies, designing the period costumes for such films as Oro, Plata, Mata and Gumising Ka, Maruja, and also helped design TV commercials and calendars.

Symbol, Sources, Surfaces, Space and Silhouettes

These words are keys to understanding Bernal’s process of design as presented in his exhibit. Humanities Professor Boylie A. Sarcina expounds Bernal’s five S’s of design in an interview. “He was sensitive to the budget limitations of local productions,” Sarcina continued.

Sarcina also divulged that Bernal was known for using indigenous and locally available materials for stage. Bernal harnessed the design potential of inexpensive local materials, pioneering or maximizing the use of bamboo, raw abaca, and abaca fiber, hemp twine raw, rattan chain link, gauze cacha and sytrofoams in productions such as Rajah Sulayman, Abaniko, La Traviata, Tomaneg at Aniway and Pagkahaba-haba man ng Prusisyon sa Simbahan din ang Tuloy (Much Ado About Nothing).

Symbol (Design Concept and Development)

Under SYMBOL is the selection of the key metaphor that crystallizes the director’s interpretation of the dance or theatre production.

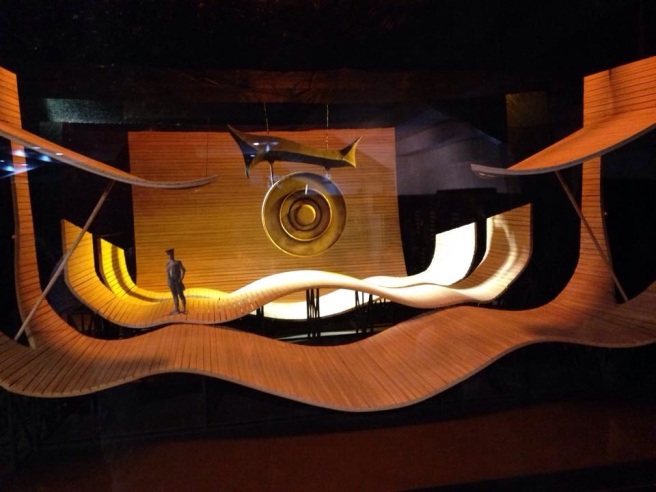

For Bernal, the process of stage design began with the identification of the design ideas or concept, that would embody or represent the thematic statement of the play or dance, as interpreted by the director or choreographer. In Odysseus, the designer chose three sails both as metonymy for the hero’s journey and as metaphor for the gods that watched over his travails and triumphs. In Paglipas ng Dilim, the three-cornered fight between the native culture, the Hispanic heritage, and the American influence was symbolized, respectively, by the free-standing nipa hut, and the Marian icon and Statue of Liberty blown up on the walls. In Sa Bunganga ng Pating, the image of the Ang Kiukok-inspired fish skeleton stood for the greed of loansharks. In Ang Pagpatay Kay Luna, the conspiracies, conflicts, and confusion of the Philippine Revolution were visualized through the metaphor of the 14 Escher-like staircases that led into a maze of levels, directions, and dead-ends. In Kung Ano’ng Ibigin, Bernal Asianized Shakespeare’s comedy by vesting both sets and costumes with Burmese and Thai motifs of clouds and dragons.

Sources (Conceptual and Visual)

For SOURCES, Bernal explored the range of sources from which he drew his design concepts and styles.

Aside from the text itself, Bernal tapped a myriad of sources for his theater designs. In DalagangBukid, Joseph Cornell’s boxes with compartments filled with “random” objects inspired the sarswela’s permanent three-level back structure, whose occasional niches alternated in showing fleeting vignettes of life in 1920’s Manila, like a student riding a bicycle or women in baro’t saya slapping mosquitoes away. To compliment the Tagalog adaptation of Puccini’s La Boheme, Bernal set the opera in contemporary Manila, highlighting a house with balcony perched atop a concrete building in Quiapo and Bistro Remedios in Malate. In The Magic Staff, children’s books inspired the intriguing pop-outs of the forest and the accordion fold-outs of the house and the trees. In the Bunkamura Romeo and Juliet, the family feud between the Montagues and the Capulets was interpreted as perennial brawls and clashes between wild animals inhabiting Tokyo’s jungle of glass, steel, and concrete. For the ASEAN touring production of Realizing Rama, the stage was do I aged by a Buddhist-inured white lotus which looked like an inverted umbrella, that could be drawn up to serve as a projection screen, lowered to reveal a hole at center for entrances and exits, or partly released to serve as backdrop for a throne room.

Surfaces (Materials, Budget, and Style)

For SURFACES, Bernal featured the local and inexpensive materials that he discovered and developed for the stage.

To execute the design concept, Bernal used material that were available, affordable, and viable on stage. For productions with substantial budget, he could splurge on real silks, lames and brocades. But for those with downright meager allocations which seemed to be the rule, he discovered affordable and readily available materials (many of them indigenous) and developed these into stage-worthy sets and costumes. In Tiyo Vanya, he stretched and stapled abaca twine in tight rows on wooden frames and stained them brown to serve as walls of a rustic house. In Rajah Sulayman, yards and yards of nito rings were hung, as backdrops or draped like curtains to one side, and accented with a huge styrofoam gong painted a glossy bronze. For Engkantada, Bernal combined bamboo and wooden planks to create the monumental holy mountain, before which danced scores of women outfitted in flowing tunics of katsa dyed in earth colors. In Philippine Circa 1907, versatile sinamay which needs neither starch nor lining to keep its shape was used to for the mutton-shaped sleeves and enormous triangular panuelos of the serpentine ensembles of the señoritas. In the pop-musical Florante at Laura, corrugated iron sheets (used for roofing) were cut into various geometric shapes, painted white, and attached to wooden platforms which could be moved to several different configurations to evoke a range of locale.

Space (Experimentation and Adaptation)

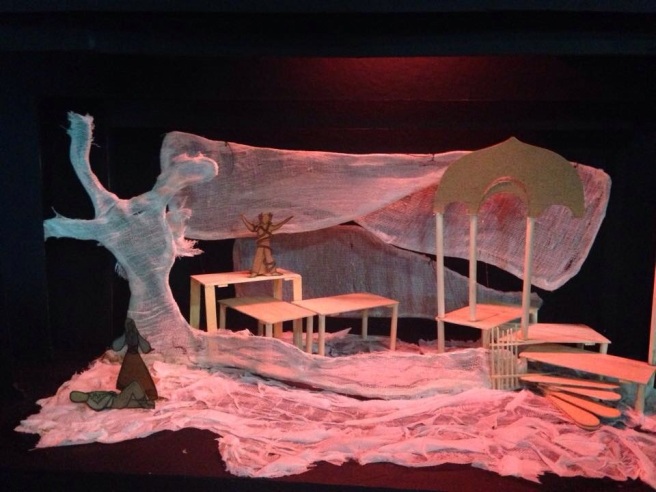

Under SPACE, Bernal’s successful experimentation with theatre space and successful solution to stage limitations is highlighted.

An important consideration for stage design is the space where the production is to be mounted. The majority of Bernal’s sets were created for proscenium stages with ample wing and fly spaces, like the CCP’s Tanghalang Aurelio V. Tolentino. But for some productions in this theater, Bernal felt he had to modify the traditional deployment of space and audience in order to bring the viewers closer to the actors. In both Lysistrata and Cyrano de Bergerac, Bernal positioned audiences on risers arranged in semicircular fashion at backstage. In Francisco Maniago, he went a step further by building three wide sandboxes on stage, the third of which jutted out over five rows of theater seats, allowing the action to “spill over the audience’s lap,” as Steve Vilaruz put it. In tiny blackboxes like the CCP’s Tanghalang Huseng Batute, Bernal designed sets which were minimal and manageable, like the single, immobile, white vehicle on which two actors played different couples traveling in Sa North Diversion Road. For Diablos which was staged in PETA’s Dulaang Rajah Sulayman, Bernal did not alter the shape, color, and texture of the walls in the historic ruins, but instead created what Denisa Reyes described as “a mythical stairway made of bamboo, plunged against the Intramuros walls into the sky”.

Silhouettes (From Realism to Fantasy)

For SILHOUETTES, Bernal’s ingenuity in dressing the actors for the stage is highlighted.

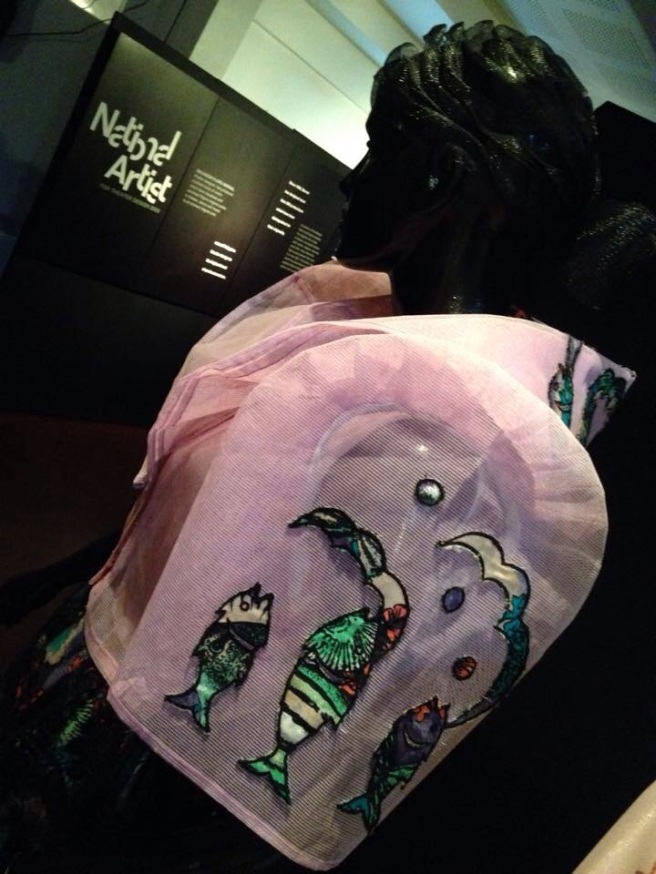

The costumes in a Bernal production generally fall into one of two categories. In the first category are those which enhance or echo the visual metaphor identified by the designer and director, as exemplified by Tibag, the verse play about the search for the Holy Cross, where the central conceit of the medieval religious icon is explicitly embodied by the voluminous, solid-looking hold lame and sumptuous brocade vestments of Elena, Constantino, and other venerable personages. In the second and larger category are garments which express or elaborate on the visual style of the production. This style may either be realistic period, stylized period, realistic contemporary, realistic stylized, and non-realistic or fantasy. Realistic period grabs strictly followed the cut, texture, decoration, and accessories of the time and milieu of the play as seen in the 1890s Maria Clara ensembles of Walang Sugat and the 1920s ternos of Ang Kiri. Stylized period frocks evoke the original period ensembles through carefully selected details of clothing or accessory but experiments with and transform the total look of the costume through the use of innovative cuts, materials, colors, accessories or design motifs, as exemplified by the stylized 16th century costumes of Ang Buhay ay Panaginip. Realistic contemporary everyday wear are donned by the expatriate characters in Bayan-Bayanan, while the realistic stylized would be exemplified by the pop children’s get-ups designed for the singing group Smokey Mountain. Non-realistic or fantasy costumes are not rooted in any specific time or place but simply materialize as figments of the designer’s imagination, as seen in the habiliments of the fairies and elves in Midsummer Night’s Dream. Whatever their category or style, costumes are always theatricalized in terms of color, decoration, or props for the stage.

Badong: The Exhibit and Workshop

The exhibit aimed to introduce and explain the art of theater design through some of the most expressive and impressive works of Bernal. It brought together three of Bernal’s closest friends and collaborators namely Dr. Nicanor Tiongson and former students Gino Gonzales and Ricardo Cruz, who are notable production and stage design experts themselves. The exhibition included a display of scale models, dioramas, costumes and video excerpts from actual productions.

A workshop on set designing for theater was held on October 3 and 4 at the Institute Mini-Theatre and was facilitated by Gonzales and Cruz to complement the exhibition.

“The exhibit and workshop hoped to inspire and encourage a new generation to take on the challenges of production design and technical theatre and aim to reach the same level of artistry Bernal has achieved,” explained Gonzales in his lecture.

The workshop was participated by 25 individuals who are members of theater groups in Iligan City.